This is a short follow-up of my post about the UK air traffic control meltdown. You might want to first read part one.

So my first post got a lot of attention, and that generates a lot of comments. What was most discussed was:

"But really though, what was the one thing that went wrong?"

Well, that depends who you ask. There was a bit of everything in the comments:

- If you ask someone who's job it is to gather requirements, and write specs, they are saying: "It wasn't made clear that waypoint names are not unique!".

- If you ask a programmer, they will say: "ha! writing buggy code!". I guess my post fell into this category; having spent a disproportionate amount of words on the bug, and a possible fix. To be clear, I've coded more than my fair share of bugs.

- If you ask a project manager or tech-lead, they might say the code review system was not thorough.

- If you ask a QA specialist they will say the system was badly tested.

- Formal methods engineers will say there was no formal verification.

- If you ask a Site Reliability Engineer they will say that the failure modes were not studied, and that the error were not traceable, etc. (There's a lot to say here.)

- If you ask a project manager, they will say the outsourcing was badly managed, that the there was not enough knowledge transfer, etc.

- If you ask a crisis management specialist, they will say the situation wasn't escalated fast enough through the lines of support, or.. (I don't know, I'm not a crisis management specialist.)

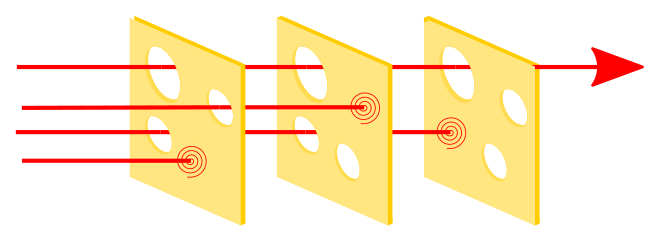

The point is, these systems are meant to not fail because they have lot of layers of protection. This is the swiss cheese model:

It likens human systems to multiple slices of Swiss cheese, which has randomly placed and sized holes in each slice, stacked side by side, in which the risk of a threat becoming a reality is mitigated by the differing layers and types of defenses which are "layered" behind each other. Therefore, in theory, lapses and weaknesses in one defense do not allow a risk to materialize (e.g. a hole in each slice in the stack aligning with holes in all other slices), since other defenses also exist (e.g. other slices of cheese), to prevent a single point of failure.

For example, if code must be coded by one programmer, reviewed by another, and tested by a third person in order to make it into production, then that's 3 slices of swiss cheese. If the probability that each of these people doesn't know about some requirement (e.g. "there can be duplicate waypoints") is 1/5, then (assuming independence)1, the probability that this lack of knowledge causes a bug to be coded that makes it through these three slices is 1/125.

It took several failures for the crisis to manifest. What went wrong was that many things went wrong.

So that's the question that NATS, the enquiry, and the wider community has to grapple with: what has gone wrong, to lead to a situation where many things can go wrong?

Other posts: part one and part three.

This is a bit naive, and it's why when developping systems where there is a primary and a backup, the teams developping them are sometimes kept completely seperated: different locations, not allowed to talk to each other about work, etc.